Following the breadcrumbs: How 1990, 1995 MLB seasons could explain what 2020 has in store

There’s no denying it – when it starts, the 2020 season will be like no other.

A 60-game season, with rule changes, a universal DH and regional opponents make this season unlike any in the sports history.

In a game where stats, matchups and trends are crucial for evaluation, how does a shortened season affect those numbers? Teams are built on 162-game figures. A strong two-week performance by a young prospect one season doesn’t translate to a full-time starting role the next. The ebbs and flows of a 162-game season will eventually reveal who a player is.

So, how do you go about looking at a team when the statistical comparisons won’t be apples to apples? It’s tricky, but the answer might lie in other seasons that were shortened or had spring trainings altered, like the 1990 and 1995 seasons. The 1990 season had almost all of spring training wiped out due to the lockout and Opening Day was pushed back. In 1995, the season started late due to the labor dispute that started in August of the previous year.

The 1995 season was shortened to 144 games and didn’t begin until late April. The 1990 season, meanwhile, had a full-length season, but spring training was roughly 3 weeks, as the 32-day lockout ended on March 19 and the season began on April 9.

It’s worth looking at the first 30 games of the season, when the effects of an altered spring training can really be felt for teams. The 1990 season saw offensive spikes in the first 30 games of the season compared to the season before and after. The 1995 season, meanwhile, saw a spike in 1st inning run production throughout the season.

Looking at those two seasons could give us a perspective of what to expect and how to potentially tackle the 2020 season.

1990 & 1995

It’s tough imagining a situation in which a spring training 2.0 — or “Summer Training” if you prefer — doesn’t have some sort of effect on both hitters and pitchers. When the season was postponed on March 12, players across the league were hitting their stride; hitters were rediscovering their rhythm and pitchers were finally stretching out their arms as they prepared for an Opening Day just a couple of weeks away.

Now, most of the players are returning to their respective team’s cities, not likely near the shape they were in in mid-March. Sure, they were able to work out from their homes and take batting practices in cages they may have, but there’s no replication for live pitching. Conversely for pitchers, they haven’t been able to throw with their catchers and were in a more static state after throwing and facing live hitters for nearly a month in spring training. It can be a tricky time for pitchers in terms of how to stay in shape and what to do.

Hall of Famer Greg Maddux told Ryan Dempster on Off the Mound that if he were still active, he would have treated his time away from team like the tail end of the offseason for him.

“I think I’d be doing what I’d be doing in January,” Maddux said. “I would try and play some long toss and if I can get on a mound once a week, I’d do that. I’d just treat it like January until the phone rings and they say we’re going to start back up again.”

Maddux would know, too. The 1990 lockout affected him right out of the gate. He was preparing for his fourth full major league season at the time.

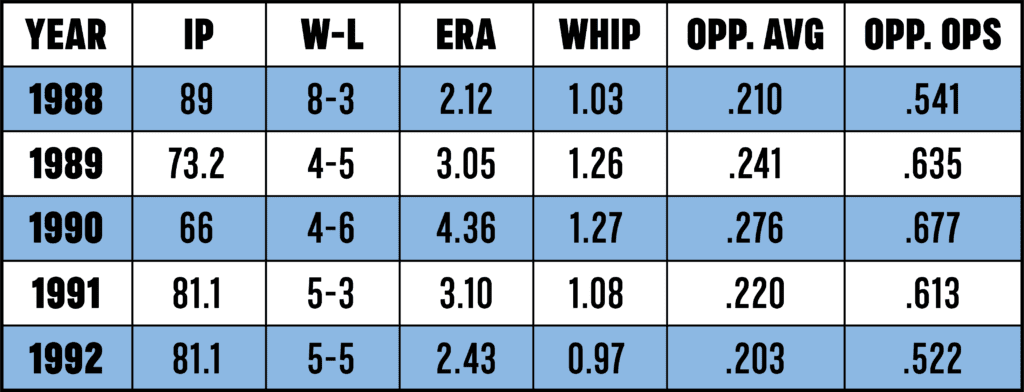

Here’s how Maddux’s numbers looked in his first 11 starts from 1988 to 1992.

“You’re going to have to get ready pretty quick once the bell rings,” Maddux said. “You probably want to continue to throw.”

Maddux wasn’t alone in watching his numbers balloon.

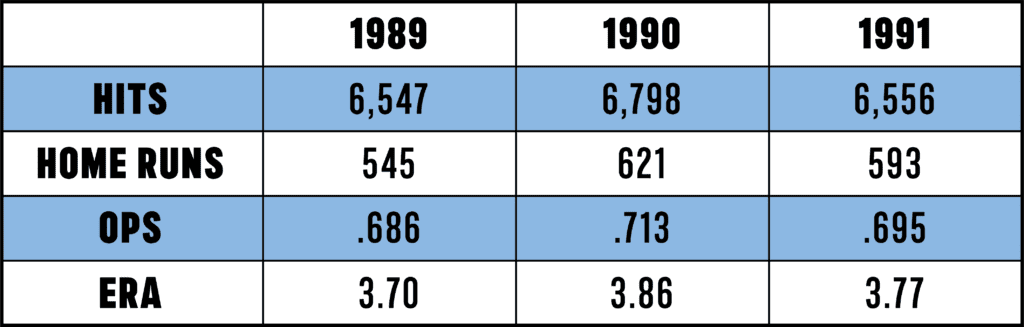

As a whole, the league saw some bumps in offensive production that year, compared to 1989 and 1991. Hitters benefitted from the shortened spring training.

In 1990, the average runs scored per game in the first 30 games of the year for teams was 8.35 — a spike from 7.96 in 1989. The runs scored per game in the first 30 games for teams dropped back down to 7.96 in 1991.

Here’s how overall season offensive numbers rose in the first 30 games of 1990 compared to the season before and after:

The 1995 season, a shortened season with a delayed spring training, saw boons in 1st inning production.

As a whole, offenses scored 1.26 runs in the 1st innings, a slight bump from the 1.22 average runs scored in the 1st in 1994, but that season was shortened to 114 games because of the players’ strike at the end of the year. So, comparing it to 1992 and 1993, the last full seasons, it was a bigger spike. In 1992, there were an average of 1.04 runs in the 1st and 1.18 runs in 1993.

Home runs were also up in 1995, with 482 hit in the 1st inning, compared to 455 in 1993 and 330 in 1992. There was, on average, a home run every 37 plate appearances in 1995, compared to a homer every 43.53 plate appearances in 1993 and a homer every 54.71 plate appearances in 1995.

It’s important to note that the boom in home run production and run production in 1995 can’t entirely be attributed to the delayed spring training — this was around the beginning of the Steroid Era in baseball where there was an uptick in 1st inning home run production — and therefore run production — after 1995.

2020 Cubs

So, what does that mean for a 2020 season for the Cubs? Well, if 2020 is anything like 1990 or 1995 — or a mixture of the two for that matter — it could mean relying on some unorthodox methods.

First-year manager David Ross had already penciled in Kris Bryant as his leadoff hitter, with Anthony Rizzo, Javy Báez and Kyle Schwarber hitting behind him. If 1st inning run and home run productions bump — especially early on, it’s crucial that the Cubs’ best hitters get as many plate appearances as early and as often as possible. In a 60-game season, a strong start is crucial to any success.

In 2019, Bryant, Rizzo, Báez, Schwarber and Willson Contreras combined to slug 149 home runs with an .887 OPS and 412 RBI. Facing a pitcher early, when they’re more likely to give up runs, will suit the quintet well.

Conversely, though, it’s imperative the Cubs pitching doesn’t give that production back up in the other half of the 1st inning.

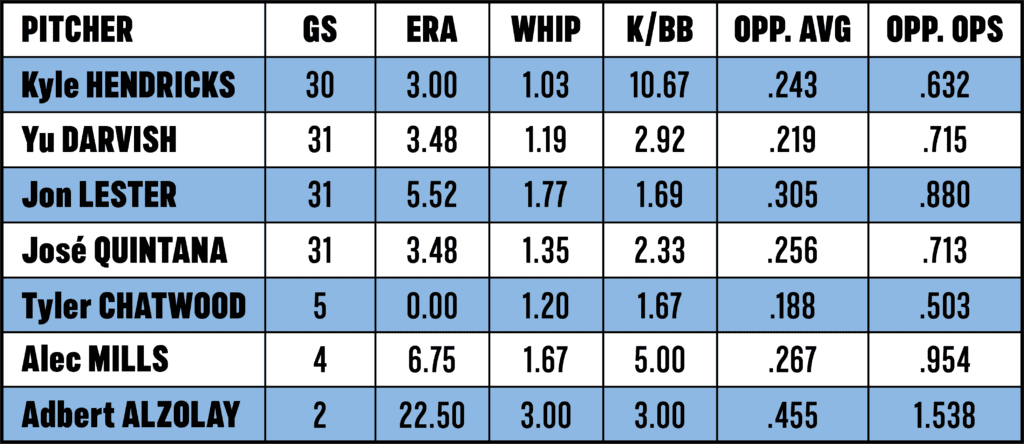

Strong 1st inning starts are important for the Cubs staff. So, could that mean the use of an opener instead of a traditional 5-man rotation? To determine that, it’s important to look at how the Cubs’ staff performs in the opening inning in 2019:

Cole Hamels (27) and Derek Holland (1) started the other 28 games for the Cubs in 2019.

On the basis of it, the opener could make some sense. Relievers like Dan Winkler, Kyle Ryan, Rowan Wick and Jeremy Jeffress – who was used as an opener for the Brewers in 2017 in a game against the Marlins – could be used from time to time to get 3 or 6 outs to start the game, especially if matchups line up.

Lester, who struggled in the 1st inning in 2019, would seemingly benefit the most from the use of an opener in his starts given his 1st inning numbers in 2019. However, Lester mentioned on Off The Mound with Ryan Dempster, the difficulties he had coming in relief in Game 7 of the 2016 World Series.

“To be down there [in the bullpen] and actually wait for that phone to ring,” Lester said. “Just sitting around and when it rings, it’s like, ‘Hey, you need to get going.’ It’s a feeling that I don’t like, to be honest. Like I said after that game, I give all the respect to what relievers do day in and day out when that phone rings.”

Could the opener work? Sure, but it might not be a complete solution for the Cubs. While using Alec Mills, Rule 5 draft pick Trevor Megill or another reliever as early inning openers could work from time to time, it doesn’t seem to be a long-term solution.

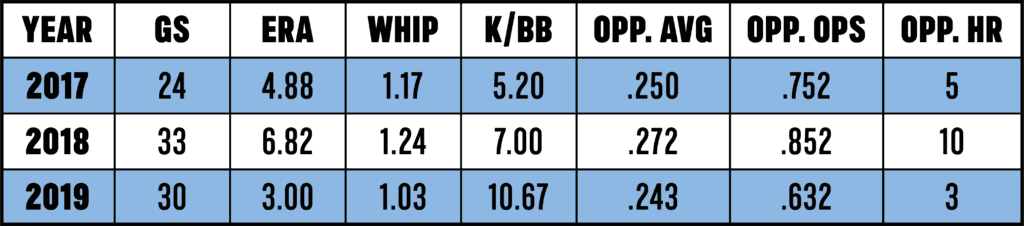

Hendricks struggled mightily in the 1st inning in 2017 and 2018. Take a look at his numbers and compare them to 2019.

So, what changed in 2019? His preparation and mindset.

“Just trying to change something up routine-wise — trying to get myself in a better mindset going into that 1st inning,” Hendricks said in April of 2019. “That seems to be where I’m making my bad pitches. Maybe try and change something up in my pregame. That way I can go out with an aggressive mindset making pitches right out of the gate and not just getting loose.”

That included using associate pitching coach Mike Borzello and bullpen catcher Chad Noble to stand in the batter’s box while he warmed up in the bullpen.

“I’m throwing the same amount of pitches [as a normal bullpen], but at the end, I’m facing two, three, four hitters and going through who I would be facing coming up,” Hendricks said in 2019. “It’s sequencing — making pitches and not just getting warmed up.”

Everything, especially in a shortened season is on the table for the Cubs. This year, a four or five-game stretch could make or break a season, so any advantage the Cubs can get is crucial.

A hot start and first inning performances will be crucial if the Cubs hope to reach the playoffs.