Top 30 Cubs prospects: 2023 preseason update

Lance Brozdowski is a player development analyst for Marquee Sports Network. Below is Lance’s list of the Top 30 Cubs prospects as the organization kicks off the 2023 season. For more on the Cubs prospects all year long, follow Lance on twitter @lancebroz.

When an organization replaces decision makers, it takes a few years before the results trickle up to the major league level. The Cubs hired Craig Breslow as a strategist prior to the 2019 season before promoting him to Assistant General Manager in the winter of 2020. After years of struggling to develop pitching, the Cubs saw contributions from players like Justin Steele, Adrian Sampson, Javier Assad and Keegan Thompson last season. Each possessing some tweak which helped them achieve success. The major league pitching staff, as a whole, posted the second-best ERA in baseball during the second half of last season.

The Cubs also hired Justin Stone as their director of hitting during the winter of 2020. His first season in the organization overlapped with the COVID-19 pandemic. This past season, however, clear signs of improvement have emerged. The Cubs made the second-biggest jump in xwOBA among all organizations, considering the four levels between Class A and Triple-A. Think of xwOBA as one of the many ways to value long-term offensive production, as it leverages exit velocity, launch angle and sprint speed rather than purely results-based information like singles and doubles. That jump moved the organization from 27th in MLB in xwOBA to tied for 7th.

The impacts of Breslow and Stone and the development staffs both have hired to lean on cannot be understated.

New for this year…

Each year I try my best to add something new. It’s no secret that my list is data driven, and I think it’s important to show my work with some of the data I look at.

This season, I’ll be incorporating “90th percentile exit velocity” into my hitter evaluations. This metric is more valuable than looking at purely average exit velocity or max exit velocity. It takes all of a hitter’s batted balls, filters for the 10% which have been hit the hardest, and finds the average exit velocity of just that 10%. The major league average for this statistic was 103.8 mph in 2022 (minimum 55 batted ball events). From looking at minor league averages on 90th percentile exit velocity, you’d expect a hitter to add about 1 mph to this metric every level he jumps, with Triple-A and MLB being similar. So if you’re a hitter in High-A South Bend and your 90th EV is 102 mph, you’d expect it to jump to 103 mph by Double-A and 104 mph by Triple-A.

Is the metric perfect? No. Is there some error to it based on the variance of hardware calibration park to park? Yes. But even if it’s not perfect, it’s more valuable to see this number than not see it at all. And it’s a big part of my evaluation of hitters.

Just like last year, I’ll be posting Stuff+ numbers for pitchers. Stuff+ tells you based on the velocity, movement and some basic release characteristics of a given pitch, how does it compare to similar pitches historically at the major league level? The number 100 is average. A fastball that has a 120 Stuff+ is 20% better than the average fastball at the major league level inside the pitcher’s window of velocity for throwing the pitch. Changeups are a perennial bugaboo for Stuff+ models, I will try to detail when a changeup below deviates from a Stuff+ score that seems underwhelming.

I’ll also be adding in-zone rate for given pitches. This is the best I can do at the minor league level for some kind of proxy of command. This doesn’t control for the velocity and movement of the pitch. Command is still a pretty ambiguous topic in the development space, but on a very simple level, if you throw something harder, with more movement, it’s tougher to locate the pitch. Here are the major league averages for how often they’re in the zone: Fastball – 54%, Cutter – 50%, Slider – 44%, Changeup – 39%, Curveball – 44%.

Here’s a rundown of the list before we dig in player by player:

1 Pete Crow-Armstrong, OF

2 Kevin Alcántara, OF

3 Hayden Wesneski, RHP

4 Benjamin Brown, RHP

5 Jordan Wicks, LHP

6 Owen Caissie, OF

7 Alexander Canario, OF

8 Matt Mervis, 1B

9 Daniel Palencia, RHP

10 Brennen Davis, OF

11 Cade Horton, RHP

12 Cristian Hernández, SS

13 James Triantos, INF

14 Ed Howard, SS

15 DJ Herz, LHP

16 Miguel Amaya, C

17 Drew Gray, LHP

18 Jackson Ferris, LHP

19 Yohendrick Piñango, OF

20 Kohl Franklin, RHP

21 Ryan Jensen, RHP

22 Cam Sanders, RHP

23 Caleb Kilian, RHP

24 Moises Ballesteros, C

25 Porter Hodge, RHP

26 Jefferson Rojas, SS

27 Jeremiah Estrada, RHP

28 Zachary Leigh, RHP

29 Kevin Made, SS

30 Luis Devers, RHP

Check out past lists:

Top 25 Prospects: 2022 midseason

Top 25 Prospects: 2022 preseason

Top 20 Prospects: 2021 mid-year rankings

Top 20 Prospects: 2021 preseason

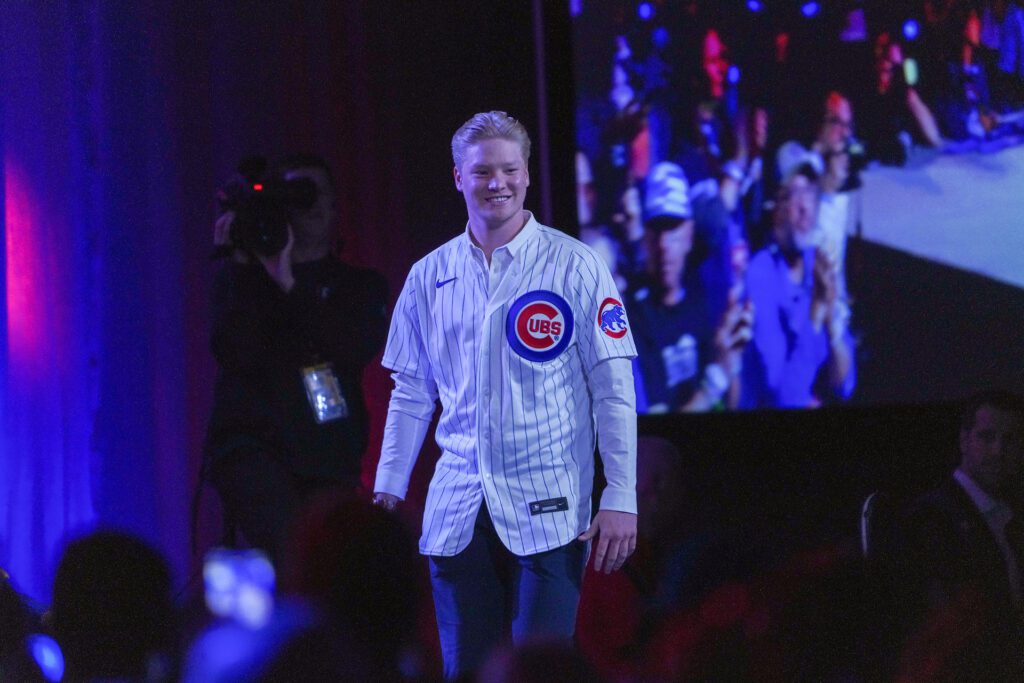

1. Pete Crow-Armstrong, OF

Highest Level Reached: High-A South Bend

90th Pct Exit Velocity: 102.3 mph

Crow-Armstrong possesses a mix of average to elite tools, with a profile that has an incredibly high floor due to his gold-glove caliber defense.

Crow-Armstrong started 2022 with a conservative approach that eventually evolved into pure aggression by mid season. It eventually settled on something in between the two. The Harvard-Westlake graduate used to be considered an OBP machine, but his swing change and power jump after making a swing adjustment unlocked a higher offensive ceiling than previously considered.

PCA’s ability to make these subtle adjustments to his aggression speaks volumes to his awareness at the plate, even at just the age of 20 years old. There is a version of PCA where he walks back some of his aggression and posts an OBP north of .350. There’s also a scenario where his career approach resembles more of the Braves’ Michael Harris II, where his aggression allows for more balls in play, more home runs and a higher average, but likely some susceptibility to swing-and-miss and larger year-over-year variance. Then there’s a goldilocks zone, where the OBP remains above the league average and he gets to more power than expected. Although this is less likely than either of the two other outcomes, it would be the scenario where he goes from an all-star and gold glover to consistently earning MVP votes.

There isn’t much to say about Crow-Armstrong’s glove that hasn’t already been said. Our friend Jim Callis and the crew over at MLB Pipeline gave Crow-Armstrong an 80 grade on his glove. This grade is rarely given to any tool because of what it means: his glove is better than .1% of the defensive center fielders at the major league level. Take a sample of 1,000 major league defenders and there’s likely only 1 glove in there which could be considered an 80. In talking with a pro scout, he questioned whether there was even an 80 defender at the major league level right now. Andrelton Simmons (during his peak) was a name that came up, so did Andruw Jones. The expectation is that Crow-Armstrong will win multiple Gold Gloves.

2. Kevin Alcántara, OF

Highest level reached: Class A Myrtle Beach

90th pct Exit Velocity: 102.1 mph

Alcántara is an explosive, long-limbed outfielder with the highest offensive ceiling in the organization.

Analyzing Alcántara prior to seeing his 2023 batted-ball numbers is a tough position to be in. The 6-foot-6 outfielder added muscle this offseason, but has stressed the desire to retain as much of his speed as possible in doing so. The hardest ball he hit last season clocked in at 112.5 mph, which is right around the major league average. There are rumors he has hit balls 114-115 mph in batting practice during Spring Training in Arizona. If this is the case and he can replicate it in game, he’d be creeping into the top 30 hitters in major league baseball… as a 20-year-old headed to High-A South Bend.

Bat speed becomes much harder to generate once (or perhaps “if”) he’s hitting balls 114 mph-plus. So the focus would turn to his approach or as it’s called in many organizations internally, swing decisions. The Cubs will probably give him the next two years in the minor leagues to refine this approach and work around better pitchers hammering him up-and-in. He chased pitches out of the zone above the Class A average last year. He also made contact at a below-average rate for a Class A hitter. It’s not necessarily concerning, given how hard he hits the ball there, will be more tolerance for swing and miss (see Pirates shortstop Oneil Cruz). But this distinction in approach will become the difference between him actualizing a large percentage of his offensive upside and hitting his more average projection, which is still probably a 20-plus homer, everyday outfield bat, just with more swing and miss than desired.

More: Kevin Alcántara talks through his swing

3. Hayden Wesneski, RHP

Highest level reached: MLB

Four-Seam: 79 Stuff+, 54% In-Zone

Sinker: 104 Stuff+, 60% In-Zone

Cutter: 98 Stuff+, 61% In-Zone

Slider: 134 Stuff+, 50% In-Zone

Changeup: 112 Stuff+, 53% In-Zone

Wesneski possesses some of the best small-sample command on his sweeping slider in all of baseball, with enough average pitches and plus command to project safely as a long-term number 3 starter.

Wesneski’s debut last season was nothing short of spectacular. His command and pitch mix allow a repertoire of relatively average pitches to play way up.

In this industry, we often idolize the idea of command, stating it’s really the only thing a pitcher needs to succeed. “A well placed 88-mph fastball is better than 95 mph.” Thoughts like that don’t consider something that is essential to pitching analysis – the shape of a pitch, how much it’s moving vertically and horizontally in combination with basic release height characteristics. This is often just referred to as “stuff.” Stuff is easier to develop because we have more specific tools to measure it, making command in young pitchers a preference for some. The Cleveland Guardians are known for this on the amateur side, and Cubs GM Carter Hawkins used to be in that organization. But to say that command is all you need is missing the point.

The vast majority of pitchers possess some balance of both stuff and command. Think of it as how reliant your stuff is on your command. Better stuff needs less command, and worse stuff needs more command. Stuff alone gives you more room for error when pitches aren’t located ideally. For example, the Rays were one of the first teams to have catchers set up middle-middle for their pitchers, essentially saying, “you stuff is good enough to live over the middle of the plate, stop trying to pick corners.”

For Wesneski, his placement on that spectrum leans towards the command side of things. But the key to it all working are his sinker and cutter grading out as near-average pitches. There are rumors of some interest in adjusting his four-seamer to possess more lift as well, which would benefit the pitch a lot.

Three paragraphs on Wesneski with no mention of his slider is a new world record (unverified). The pitch is a sweeper, but thrown with a slightly different grip than the two-seam orientation that has become popular among organizations (seen here). That means it picks up a lot of lateral movement at a good velocity. Wesneski’s is usually 81-83 mph with 18” of glove-side movement. It’s a pitch that rates out 30% better than the average breaking ball and plays up because of his rare feel for commanding the pitch. Among a sample of 470 pitchers last year who threw 30-plus innings, Wesneski was the 10th-best pitcher in MLB locating his slider. He was also the only pitcher in the top 10 of location that generated more than 13 inches of lateral break. Generally speaking, the more spin-induced movement a pitch has, the harder it is to command. Wesneski is an outlier with his slider feel.

The only worry here is that given the infancy of most public command or location tools, there is limited information publicly about how command ages for the average pitcher. It may be bold to aggressively rank Wesneski relative to the industry due in part to how important fastball quality is to the projectability of a starting pitcher, which I will touch on continually throughout this piece. Even if the current info we have overstates some of Wesneski’s strengths, his comfortability with data, mechanics and self awareness create confidence that he’ll linger closer to his ceiling as a player even if pieces of the puzzle fall off over time.

4. Benjamin Brown, RHP

Highest level reached: Double-A Tennessee

Four-Seam: 110 Stuff+, 57% In-Zone

Slider: 96 Stuff+, 48% In-Zone

Curveball: 106 Stuff+, 51% In-Zone

Brown comes into the organization as a fastball-curveball pitcher. The Cubs will add a slider and likely revive his changeup to bolster a sure-fire starting pitcher.

Brown, like Alcántara, is another player on this list who is tough to rank given the tweaks the organization will make to his profile. And the absence of data before we get to the end of April, makes my data-heavy approach to lists a bit tricky. His approach is based around a four-seam fastball that grades out well and sat 95 mph in Tennessee last season. The pitch has above-average arm-side movement, which makes it a bit better at attacking right-handed hitters than left-handed hitters. This raises the question of whether he’d add something with a bit more cut to help against left-handed hitters, or whether there’s some fastball differentiation to unlock, where a two-seam works versus right-handed hitters and more true four-seam can live versus left-handed hitters.

In conversation with Brown, he’ll say he threw only one breaking ball last year — a curveball. Yet movement plots show a mildly distinct slider that had extra lift, was thrown a bit harder and didn’t grade out as good as the curveball. This could have just been a handedness thing, where the location of the pitch facing right-handers versus left-handers changed the resulting shape. But regardless, models didn’t love the “slider” and the Cubs have handed him a sweeper (something they have done to numerous pitchers on this list as you’ll see). Stuff+ models love sweeping sliders, so it wouldn’t be a surprise to see that slider rating jump from 96 to 120. Given his strike-throwing ability, I would imagine his in-zone rate on the pitch will eventually be strong, but hiccups initially wouldn’t be surprising.

How the sweeper affects the rest of his repertoire is a question. Does he change the curveball he’s very comfortable throwing for strikes to embrace more drop and lower velocity (unlikely)? Does he tinker with some kind of “bridge” slider between the curveball and sweeper (more likely)? With the prevalence of pitchers adding bullet or gyro sliders–something that has more drop than a cutter and less sweep than a usual slider–to repertoire in tandem with sweepers, I would guess the ideal repertoire mixes in a third breaking ball of some kind. Then there’s a changeup, which he worked on in the past at Driveline Baseball, a third-party player development organization, that was scrapped with the Phillies. Given his fastball shape, there’s probably some major league average version of a changeup to help him even more versus left-handed hitters.

The clear potential for multiple above-average pitches built around a good fastball and an ability to get everything in the zone gives him a prototype starting pitcher framework. The Cubs will have fun tinkering with his mix.

5. Jordan Wicks, LHP

Highest level reached: Double-A Tennessee

Four-Seam: 116 Stuff+, 57% In-Zone

Changeup: 108 Stuff+, 41% In-Zone

Slider: 137 Stuff+, 40% In-Zone

Curveball: 82 Stuff+, 37% In-Zone

Wicks has one of the best changeups in the organization, a new slider that the data loves and better-than-average command. A velocity uptick would benefit his profile immensely.

It seems appropriate to start Wicks’ write-up by talking about changeups. In analyzing this pitch generally, you want to look at it in relation to a pitcher’s primary fastball. While this can provide some extra information when analyzing something like a slider, it’s most important for changeups. The two variables that matter most are the velocity separation between the two pitches and the drop separation between the two pitches. Changeups that have good vertical break separation, say over 10 inches of difference, create a lot of ground balls (think Zack Greinke). Changeups that have good velocity separation, say over 8 mph of difference, are better at generating whiffs (think Dylan Cease).

Most changeups are some combination of both, as is the case with Wicks’. He separates his changeup from his fastball by more than 10 mph and more than 10 inches. That’s a recipe for a great pitch and the results agree. It lingered around the 50% mark in terms of whiffs per swing, where 30% is the MLB average.

Wicks’ slider, which he developed entering 2022, highlights why something like Stuff+ isn’t capturing everything about a given pitch. Stuff models believe it’s a good pitch because it’s creating a lot of lateral movement and it’s thrown with adequate velocity. When I ranked and wrote about Wicks last year, knowing this pitch was coming into his repertoire, I was extremely excited for what it would do to his profile. The results were good, generating a 37% swing-and-miss rate, right around average for a Double-A level slider, but some have mentioned the pitch doesn’t visually impress as much as you’d expect, drawing more average grades from scouts.

My guess is that this has something to do with how the pitch sits in the context of his repertoire or maybe something more nuanced like how it breaks off his arm angle. A recent piece by Prospects Live points out that the horizontal separation between a slider and fastball can create some issues if it gets too large. Hitters may have a better ability to pick up the difference between these pitches earlier in ball flight (the Mariners pitcher Matt Brash has a slider which you could argue is the best “stuff” pitch in baseball and yet he posted an ERA north of 4.40 last year).

It seems logical that a “bridge” pitch like a true cutter or something with more drop, like a second slider, could fit his repertoire nicely. Given the ease of adding cutters in a pitcher’s repertoire, often due to the orientation of the ball creating the shape while the pitcher just thinks “fastball,” the bigger variable to conquer first is adding velocity.

If Wicks sat 94 instead of the 92 he sat last season, all his stuff grades would go up by more than 5 points. His margin for error when pitches are in the zone would improve. His swing and miss will likely improve as well. The biggest gains from velocity come when crossing the 93 mph threshold, which makes it such an important fence for Wicks to hop over in his career. My bet in ranking Wicks here is that this velocity uptick eventually happens. I’m unsure when it will or if it’s even something the Cubs have thought about internally, but it’s the single most important thing to raising his ceiling at the major league level.

6. Owen Caissie, OF

Highest level reached: High-A South Bend

90th pct Exit Velocity: 106.8 mph

Caissie possesses exceptional bat speed and the ability to hit the ball hard with manageable discipline at the plate. It’s an offensive-heavy profile that will have some kind of major league role.

Yes, you’re reading that correctly. Owen Caissie does in fact hit the ball harder on average than nearly every other Cubs prospect, sitting with a 90th percentile exit velocity that would be good for a tick above the major league average. A strikeout rate above 28% in High-A might look a bit scary, but he balances it out with a walk rate that has consistently been above 10% in his minor league career. The differential is enough to work with at the major league level, suggesting that unlike a Pete Crow-Armstrong, where his batting average may drive his profile, we’re looking at more of a profile supported by OBP and the ability to get to power in game.

The upside comes from the underlying stats that make up Caissie’s strikeout and walk rates. He swings and misses at a clip slightly above the average for High-A, he makes contact at an above average rate for the level and he only chases slightly more than the average High-A hitter. The foundation is here for Caissie to ascend to a level of development where the focus becomes refining swing decisions rather than reworking his swing or trying to add bat speed, which many hitters are still doing at his age.

This phase is also probably the most ambiguous. It’s similar to command for pitchers, where bat speed is something like a pitcher’s velocity. There’s an idea of how to train bat speed and improve it. Adding weighted bats to a program in a way that’s similar to weighted balls. Whereas leaps in swing decisions come about a bit more randomly, potentially tied to how good a mental map a hitter has built of advanced-level pitching. This is supported by data suggesting that year over year, swing decisions possess more randomness. In a way, it’s great that Caissie already has major league average power, because it may take some time to refine his approach and actualize as much of his offensive ceiling as possible.

Caissie’s defensive position is a corner outfield spot or first base. Scouts who saw him last year have critiqued his defense, but his arm gets average grades, suggesting that he’d benefit from good defensive positioning to make up for his lack of straight-line speed. He’s also only 20 years old and we’ve seen players change their stripes defensively throughout their careers (Julio Rodriguez was once thought of as an average runner). Even if Caissie is destined for first base long term, an early-career stint in the outfield, even if it’s slightly below average performance, would do wonders for his value.

7. Alexander Canario, OF

Highest level reached: Triple-A Iowa

90th pct Exit Velocity: 106.9 mph

Canario has light-tower power and developed a keen eye at the plate. Next to Alcántara, he has the most offensive upside in the organization.

If Canario hadn’t sustained a freaky injury in the Dominican Winter League this offseason, he would have been my #4 prospect in this system. He has exceptional power with excellent underlying batted-ball stats to back it up. As he ascended through the minor leagues last season, his chase rate started to plummet. Perhaps this was a product of seeing less competitive pitches given the tare he had been on, but falling from around 30% chase out of the zone to the 23% by the time he got to Triple-A is notable.

This adjustment in approach at the plate vaults him into a stand-out combination of power and approach, allowing for pretty easy tolerance of any contact concerns he may have had in the past. The concern is that small-sample approach changes can often lead analysts astray. There has been research done, which I linked to in Caissie’s blurb, showing that year-over-year changes in swing decisions (think chase rate or discipline) fluctuate by material amounts when compared to something like how hard you hit the ball. So while it might be easy to overreact to an approach change like Canario’s, there is more evidence to suggest he holds something closer to an 8% walk rate at the major league level than the 16% he showed in 84 PA at Triple-A. This difference swings his value if you hold his power constant, ranging from something like a 1.5-2 WAR player to more in the ceiling window of 3.5-4 WAR if the discipline holds. Regardless, there feels like some middle-of-the-order role here for a Cubs team that has lacked power over the last few seasons.

It’s difficult to aggressively rank Canario given the chance not all of the power comes back, or it takes more time to come back after his injury. This rank is a hedge between both results with more of an admiration for how hard he was hitting the ball. I expect him to rise on this list if his batted-ball data looks good by the end of the year.

8. Matt Mervis, 1B

Highest level reached: Triple-A Iowa

90th pct Exit Velocity: 105.8 mph

Mervis won the Cubs minor league player of the year award after a torrid season across three levels of the minors. His mix of feel for the zone, contact and power makes him a high-floor major leaguer.

Mervis is a divisive prospect in the industry. He’s the exact kind of player that calls your bluff as an analyst. He wasn’t thought of as a big prospect as an undrafted free agent out of the shortened 2020 draft. And yet he posted an exceptional 2022 season: 36 home runs, 119 RBI and an improved strikeout rate each time the Cubs promoted him. So after watching his production and seeing the adjustments, how much do you correct your priors? For me, the answer is a decent amount.

The things working against him are the negative positional adjustment that a first baseman gets, given he won’t be playing any outfield like Canario or Owen Caissie. A 17-HR, .310-OBP center fielder who plays average defense will be more valuable from the perspective of a statistic like Wins Above Replacement (WAR) than a 30-HR, .310-OBP first baseman who is a league average defender (other things aside). The offensive bar is simply higher.

Mervis also hits the ball hard, but it’s more around the average for a major league hitter than well above average like Canario or Caissie. 90th percentile exit velocity is valuable because it increases a hitter’s margin for error. Hit the ball harder, more good things will generally happen. If you hit the ball around average, there’s a strong chance you need to do something else to make the profile work. But it’s not everything, particularly for a hitter like Mervis. For example, two of the game’s best hitters have a 90th percentile average exit velocity that is league average: Mookie Betts and Nolan Arenado. But both pull a large margin of their fly balls with below average chase rates, which allows them to post slugging percentages well above the major league average and perform as two of the league’s best hitters. Another more nuanced metric is something like how much a hitter varies their launch angle, generally a tighter launch angle allows for more production on balls in play (more on that here).

There are a lot of ways to rationalize Mervis being some kind of major league player at 1B and it starts by leaning into something else he does well not being captured in the limited hitter data we have, even at the major league level. I expect his profile to be something more like 20-25 HR with good discipline in MLB as opposed to the 30-plus home runs he put together through three levels this season.

9. Daniel Palencia, RHP

Highest level reached: High-A South Bend

Four-Seam: 132 Stuff+, 52% In-Zone

Slider: 106 Stuff+, 43% In-Zone

Changeup: 85 Stuff+, 32% In-Zone

Palencia has a fastball that averages 98 mph and a slider that sits 88-90 mph. It’s a two-pitch mix that has starter potential even if the peripheral pitches in his repertoire never manifest.

The dominance of pitchers like Hunter Greene and Spencer Strider, both two-pitch starters, has reopened the debate of whether a pitcher really needs a third pitch. The gut answer is “of course,” but I think the debate overall is more nuanced. Most players in baseball aren’t blessed with a fastball that averages around 100 mph like Greene or has ride from a low release height like Strider. If you are, and can just throw some kind of slider hard, you have the blueprint of a major league starter… even if you don’t really have a third weapon.

Palencia’s fastball averaged 17” of vertical movement by the end of the season, a 2” increase from earlier in the year. Vertical movement is how much a baseball resists the downward force of gravity on its way to the plate. The major league average is somewhere around 16”, but that’s before you consider velocity. Combine this velocity and movement and you’re looking at a fastball that should play incredibly well at the major league level. Consider also that fastball quality is the best indicator of major league starting pitcher success and my aggressive rank leans towards Palencia having a greater chance of becoming a starter than some might think.

Whether he actually becomes a starter, even if he’s brought up as a reliever first, hinges more on control than depth of repertoire to me. He’s an obvious candidate to throw every non-two-strike fastball over the middle of the plate and challenge hitters. You could probably envision the same for his slider. His changeup and curveball (not listed above) are both works in progress.

His curveball was hard enough last year that it was grouped into his slider shape more often than not, which may be messing up some of my info above. The goal of making that a low 80s offering with more depth is likely in progress given some of his live sessions from this spring (which you can see here). His changeup didn’t grade out well last year even though he threw it more than 10% of the time by the end of the year and he struggled to put it in the zone, making it a non-competitive pitch more times than not. And given how his slider works (it’s effective versus left-handed hitters given its lack of lateral break), he may not need another lefty-neutralizing weapon.

In a dream world, I think Palencia can be a two-slider arm, throwing his current slider alongside a sweeper, which could hopefully sit around 84 mph with 12” of horizontal break, compared to his current slider which is more 88+ mph with below 3” of break. The sweeper would help neutralize righties more than he has and this dual-slider approach is slowly taking over baseball as teams chase more swing and miss, especially given shift restrictions, as opposed to weak-contact-inducing cutters, which generally have more backspin (more on that combo here).

My plan was to have the most aggressive rank on Palencia in the industry. My only regret is that I might be too low.

10. Brennen Davis

Highest level reached: Triple-A Iowa

90th pct Exit Velocity in 2021: 103.7 mph

Davis had surgery to remove a ‘vascular malformation’ in his back, which showed it’s strain on his batted-ball data by the end of the season. If he bounces back, this rank will be too much of a correction down.

Davis is the hardest player in this system to rank without knowing what his batted-ball data looks like early in spring. Two months during the middle of last season with minimal to no loading of his back in compound exercises (like back squats) took a toll on his strength when he returned. But that was assumed. The positive in his return is that he looked like the same hitter from an approach perspective at the plate.

Even after his surgery, he made above average contact for the Triple-A level, swung and missed less than average and didn’t chase out of the zone at an alarming rate. Combine that with the ability to post average major league power numbers and play a corner outfield spot better than anybody above him on this list (not named PCA) is the reason why I held him as the #1 prospect in the system in my midseason update. His rank at 10 now is a correction that looks worse than it is given I probably should’ve had him 4th or 5th in that 2022 update.

At the moment, it all hinges on how he’s recovered and built back up strength this offseason from surgery. If everything lines up well and he looks like his 2021 self after a month or two of data, he’ll be in contention top 5 in the system again, no question. He won’t be number 1 any more given how strong the system has gotten around him, but with injuries, especially those that are uncommon, you have to assume some kind of risk that a prior version of the player no longer exists.

The best version of Davis is something like a .250-.260 hitter with an OBP around .340 and 20-25 HR a season at the major league level. It’s an extremely comfortable profile that has a chance to jump higher as his approach is refined beyond his age-23 season. There’s still probably some kind of major league role if his average takes a bit more of a hit and falls to the .240 window because that approach we talked about will always support his strong OBP profile.

His evolution and potential rebound from 2022 is one of the key things I’m watching early this season.

11. Cade Horton, RHP

Fastball: 111 Stuff+, 52% In-Zone

Slider: 111 Stuff+, 42% In-Zone

*Numbers presented above are college information

The Cubs surprised the industry with Horton’s selection 7th overall last season. He’s a young righty with a nasty slider that will be his best pitch for years to come.

There are a mix of variables that made Horton an unknown commodity during last draft season. He was coming off Tommy John surgery, had multiple versions of his slider and was a draft-eligible sophomore, making him young relative to other college pitchers. The Cubs under-slotting him at 7 overall allowed them to overslot Jackson Ferris and essentially take two shots on what could be considered the highest upside arms in the draft.

My best guess for what Horton’s slider looks like this season is something averaging 85-86 mph with around 10” of lateral break, which would push it up around 120 on the Stuff+ as opposed to the 111 you’re seeing above. It should give hitters in Class A a lot of trouble, especially if he can put it around the plate 45% of the time or more. It will be interesting to see how well High-A and Double-A hitters see the pitch (whenever those promotions come). But the more interesting question is how his fastball plays.

Horton averaged about 94 mph on the pitch last season with Oklahoma with above-average vertical break numbers, which is why you see an above-average Stuff+ score above. His results in college deviated a bit from the Stuff+ suggestion, however. He only generated about 15% swing-and-miss on the pitch, below average for a college fastball and allowed an above-average rate of hard contact at undesirable launch angles. But this was after Tommy John surgery and a period of time where he was just ripping sliders in leverage spots (like the College World Series) against hitters who were having extreme difficulty picking up the pitch. And the college baseball is also very different from what he’ll use at Class A, which will then be different from what he uses by the time he gets to Triple-A.

In sum, it’s probably best not to overreact until we see what his fastball shape is this season and how the rest of his repertoire breaks out. Given his spin characteristics, there’s a good chance he develops an above-average curveball. It sounds like there are plans for a changeup, but there’s a better chance he’s suited to mix a cutter to lefties as opposed to a changeup and embrace a very simple approach: strikeout righties and limit hard contact against lefties.

12. Cristian Hernández, SS

Highest Level Reached: Arizona Complex League

90th pct Exit Velocity: 101.9 mph

Hernández is a good bet to stick at shortstop and hits the ball hard for his age and size. He has a lot of time to correct some contact concerns and add even more strength.

A lot of international prospects possess a ton of hype based on their dollar figure coming out of international markets. As a result, they generally come in with such high expectations that everybody assumes they should be sure-fire top 5 prospects in a given system. Then comes an inevitable market correction where the player is playing stateside for the first time, away from family, facing a much better style of pitcher, growing into their body, and numerous other factors that can cause non-linear development. For example, the Yankees signed Kevin Alcántara for $1 million back in 2018 and just now we have a general consensus that he is a top-100 prospect… 5 years later.

Hernández turned 19 this past winter and struck out 30% of the time in the Arizona Complex League last season. The key is drilling into why those strikeout rates occurred. The common–but I think slightly incorrect–analysis of his approach at the plate is that it isn’t great. His out-of-zone chase numbers suggest another story. He actually had a lower chase percentage than Alcántara and Crow-Armstrong last season. Hernández struggled to make contact, particularly in the zone. The data suggests he didn’t have an issue understanding where the strike zone was, but more so actually putting bat on ball in situations when he should have.

It’s a great sign that he has quieted down his swing this season, perhaps as a way to help him correct this subtle issue and make more contact. If he makes more contact, then he’s able to get to his above-average exit velocities for his age and do damage in the way we all expected him to when he signed for big money out of the Dominican Republic.

13. James Triantos, INF

Highest Level Reached: Class A Myrtle Beach

90th pct Exit Velocity: 98.9 mph

Triantos has one of the highest contact rates among top prospects in the organization and the defensive chops to play third or second base, making him a reasonable comp offensively to a player like Nico Hoerner.

Traintos recently underwent surgery to repair a torn meniscus in his knee, likely sidelining him until the middle of summer. What he accomplished at Class A Myrtle Beach last year and his age, don’t set his timetable back much long term. The calling card of his profile is a high contact rate, hovering above 50% for all of the 2022 season, the highest in a sample over 100 balls in play for any player on this list. It allows him, especially against Class A pitching, to put a ton of balls in play and maintain a batting average around the .270 mark long term.

Much of this list prior to Triantos was filled with big power bats who hit the ball hard. Traintos is a deviation from that given his below-average 90th percentile exit velocity even when controlling for age and the Class A level. But if we assume improvement as he matures, he should be able to land somewhere under the major league average, a point that is tolerable given how much he’ll put the ball in play. Hitting the ball hard increases your margin for error. If you don’t hit the ball harder than the average player, you need to do something else in your profile to project as an average to above-average bat. Whether that be pulling a lot of fly balls, putting a lot of balls in play, or having exceptional discipline at the plate. Traintos’s best projection leans towards some combination of putting a lot of balls in play and getting to all of his power on his pull side. That is how you can envision 15 HR at the major league level.

Growth going forward for Traintos is honing in where he is swinging more to shrink down the already good gap between his strikeouts and walks. He’s hit home runs this year off pitches that were thrown at his neck. While it makes for good highlights and an astounding display of bat speed and tight rotation to inside pitches, as pitching gets better against him, the probability of that home run occurring drops considerably. He’s currently a bit like PCA in that respect, where he was swinging so much last year that some of the contact he’s making wouldn’t be considered productive even if it results in bloops and sawed-off base hits from time to time. The push and pull of that profile will be the determinant between the floor and ceiling of his profile offensively.

14. Ed Howard, SS

Highest Level Reached: High-A South Bend

90th pct Exit Velocity: 107.4 (less than 70 balls in play)

Howard showed a considerable increase in bat speed before sustaining a scary injury that shut him down for the season. If he’s able to lift the ball more, the expectations for his offensive profile rise.

Howard’s rank on this list is another that is difficult given his proximity to a significant lower-body injury. This spring, he was back on the field, throwing, running and taking live at-bats. His actions looked as good as they were pre-injury, with maybe a tick down on his explosiveness that would recover as his strength builds back up this season.

He still projects to stay on the left side of the infield long term, whether that be third base or shortstop. Time at third base would mean a raised floor for what his offensive production would need to get to in order to play full time. A long-term role at shortstop would drop that floor. Given the batted-ball increase we saw in South Bend before this injury, the chance that his offensive profile could work at third base makes a bit more sense. The only qualifier with how hard his batted balls were is that the majority of them were on the ground. Generally, it’s easier to hit the ball hard on the ground that it is in the air, so I think that number above is partially inflated. Howard’s average launch angle was one of the few in the organization among top prospects to be under 5 degrees, basically showing that most of what he hit in this sample was not ideally where you’d want your hardest-hit balls to live.

In an ideal world, he would easily trade some of his hard contact for contact that’s on the ground for slightly softer contact that’s in the air. This rank is a bet that the hitting department Justin Stone oversees can easily make this change to Howard’s bat. Even if he’s never a big power, fly-ball hitter, if he can maintain a ground-ball rate that isn’t in the 55-65% range, he can be a productive offensive shortstop or third baseman.

15. DJ Herz, LHP

Highest level reached: Double-A Tennessee

Four-Seam: 102 Stuff+, 51% In-Zone rate

Curveball: 84 Stuff+, 35% In-Zone rate

Changeup: 105 Stuff+, 45% In-Zone rate

Herz’s effectiveness isn’t properly captured in pitch data, as he lands crossfire in his delivery allowing his stuff to play above their grades. And there’s a new sweeping slider in his mix this season.

Herz is the spot on this list where one really has to consider the difference in projecting a prospect as a reliever, multi-inning reliever or starting pitcher. Herz falls somewhere in between the starting pitcher and multi-inning reliever area. Compared to every pitcher above this list, for example, I think he has the highest probability of landing as some kind of reliever long-term. This runs a bit counter to his mix, which is based heavily on a great changeup that stymies right-handed hitters and generated a 42% swing-and-miss rate last season, 8% above the average for a Double-A changeup last season.

His curveball allowed him to post staggering strikeout numbers each of the last few seasons too, but it was pretty clear that the shape wouldn’t have worked as a primary breaking ball at the major league level. So the Cubs gave him a sweeping slider, the same pitch they gave more than 10 arms this offseason (more on that here). Without seeing the shape on the pitch yet, it’s safe to say it will grade out better than his curveball and probably turn into his primary breaker by season’s end, even if command of it early isn’t sharp. Three legitimate pitches, four if you still like his curveball, and the third being a fastball that has an extremely flat approach to the plate due to his vertical break and low release height, makes his profile more starter than reliever.

The risk in guaranteeing Herz is a starter comes down to a combination of command and delivery. His crossfire delivery is something that we don’t have a large sample of success of at the major league level, which is reason alone to question it’s viability outside of a short-inning role. In regards to his command, he found the zone enough in South Bend to decimate hitters, but jumping to Double-A showed how more advanced hitter’s would approach his mix. His walk rate jumped 6% as a result. The fun variable here? Maybe Herz just couldn’t see during sunny day games. He’s an extremely light-sensitive, fair-skinned pitcher, who this offseason got red contacts that allow him to stare directly into the sun without squinting. He thinks it will help his command, and I have no reason to question that.

16. Miguel Amaya, C

Highest Level Reached: Double-A Tennessee

90th pct Exit Velocity: 103.2 mph

Amaya has dealt with injuries throughout his career, remaining steadily inside the top 20 on lists due to the potential of being an average defensive catcher with an above-average bat.

Amaya falls into the same bin as Brennen Davis and Ed Howard above him. It’s difficult to determine where a prospect’s stock currently stands without knowing how he’s recovered from a Lisfranc fracture and his recovery from Tommy John surgery (the latter of which has become less of a concern in recent years). The positive angle here, that makes me more confident in this rank is that even with the injuries, his return to action last year showed a reasonable 90th percentile exit velocity mixed with a great understanding of the strike zone. His chase rate hanging below the Triple-A league average and contact rate sitting above average provide more confidence in his floor as long as he holds average batted-ball quality.

If Amaya doesn’t end up as a catcher long term, the floor he needs to get to in order for his offensive profile to work rises a lot. For now, I still see him as a catcher with some consideration that he moves off the position. If you’re 100% convinced he’s a catcher long term, even if it’s just in a part time capacity, he probably nestles himself into the 12-13 spot on this list.

17. Drew Gray, LHP

Highest Level Reached: Arizona Complex League

Four-Seam: 85 Stuff+

Slider: 127 Stuff+

Curveball: 57 Stuff+

Changeup: 99 Stuff+

Gray is a lower slot lefty who is able to generate above-average ride or carry on his four-seam fastball despite a low release height. It’s a recipe that should give him an advantage over hitters for a long time, regardless of role.

It may seem insane for me to have the 3rd round pick from the Cubs strong 2021 draft class ahead of the $3 million lefty from the 2nd round of the 2022 class, but the rank of these two pitchers is a testament to my reliance on the data I see at the minor league level, even in small samples. Gray is doing something with his fastball that will set him up for success in the future no matter what role he takes on. In the Arizona Complex league, he averaged 17-18” of vertical movement on his four-seamer from a release height that is below the major league average. Generally, as a pitcher drops their arm slot lower, it’s more difficult to orient their wrist vertically to achieve the backspin on the ball that results in good gravity-resisting vertical movement. This is why you’ll often see over-the-top deliveries achieve the highest vertical movement numbers.

This shrewd combination Gray has results in a particularly flat approach of his fastball to the plate, meaning the majority of hitters in baseball will have difficulty catching his pitches flush on their barrel, as the ball will stay above the bat more often than not. Mix that distinct trait with a breaking ball he was spinning near 2,800 rpms, about 200 rpms above the major league average, and the raw tools are there for a starting pitcher if he can fill the zone enough.

His Tommy John recovery also gave him time to bulk and strengthen up, likely with the goal of improving his velocity, which was only 90-91 mph in his 2021 Arizona Complex League stint. If Gray comes out post-TJ sitting 93-94, he’ll push into the top 12-15 of this list with ease. If it takes a bit more time to sit 3-4 ticks above his prior velocity, I’m willing to wait for that jump to make a correction upward.

18. Jackson Ferris, LHP

Highest Level Reached: IMG Academy

Ferris is a loose and athletic southpaw with a noticeable tilt to his trunk as he releases the ball, allowing him to generate good vertical movement. It’s likely the Cubs tinker with every other pitch in his repertoire in hopes of generating first-round value out of a second-round pick.

On a data-heavy list, for me to rank Jackson Ferris more aggressively than 18, would be a detriment to my own process. I’ve never seen Ferris pitch, I’ve never scouted him, and I lack sources who got more than hearsay from others on him. There’s likely a reason the organization under-slotted Cade Horton at 7th overall to have enough money to give him just over $3 million. My gut tells me the organization sees less of a difference between Horton and Ferris than the public does in terms of future value.

My issue from an analysis standpoint on what the Cubs see in Ferris is that it’s likely tied to his movement patterns on the mound and something biomechanic. Meaning they probably already see him as an elite mover down the mound and think that with 2-3 years of tutelage with the coaches and technology that the Cubs have, he’d have a great chance to realize a higher percentile outcome of his future potential.

The data I have from his IMG Academy days doesn’t suggest any outlier pitch shape or release height characteristics, which gives me pause. I’ll be a lot more confident in my rank of Ferris come the midseason update when I can see some game information in the Arizona Complex League or hopefully Class A Myrtle Beach.

19. Yohendrick Piñango, OF

Highest Level Reached: High-A South Bend

90th pct Exit Velocity: 104.6 mph

Piñango has elite contact ability and better-than-average batted ball stats. The next phase of his development hinges on refining his swing decisions and chase-heavy approach.

Piñango remains the prospect in this system that gets overlooked the most. Maybe it’s because the overall production didn’t really wow last season, posting a line that was below the High-A offensive line. The issue in the production was the lack of extra-base hits and OBP despite a really strong ability to make contact and put the ball in play.

He’d benefit immensely from a refined approach. Currently, he’s in the James Triantos area of swinging so much that the balls he’s putting in play probably won’t be productive as he reaches higher levels (even if he does hit the ball hard). So some conscious adjustment to cut down his chase and focus on the areas of the plate he creates slugging percentage would be a boon to his profile. He’s at the phase in development where swing decision adjustments like this become the focus, given how hard he already hits the ball. But again, this phase is still the most ambiguous in development, especially if he finds relative success in the minors without being pressured to adjust.

The Cubs starting Piñango at High-A South Bend again after 110-plus games there last season with ok offensive production is probably a testament to the outfield depth the organization has built up rather than a knock on him as a player. He should ascend to Double-A soon and I expect him to have success. The key to watch is whether he can suppress his chase rate.

20. Kohl Franklin, RHP

Highest Level Reached: High-A South Bend

Four-Seam: 128 Stuff+, 45% In-Zone

Curveball: 103 Stuff+, 43% In-Zone

Changuep: 90 Stuff+, 38% In-Zone

Franklin has a great fastball and has maintained relevance due to a large uptick in velocity since entering the organization in 2018. Adding a sweeper slider gives him a great chance to generate more swing and miss versus right-handed hitters, but finding the zone more is key to his success.

Franklin harkens back to an earlier point I made in this ranking regarding the quality of a pitcher’s fastball having a large bearing on their potential as a starting pitcher. His fastball shape is great. He generates about 10% more chase on the pitch than the average High-A pitcher did last year, he also gets about average swing and miss. The general concern with everything he throws is that he’s struggled to find the zone early in the minor league career, and when his pitch has been in poor spots, he tends to allow slugging percentage more than you would like for a fastball that has this strong of underlying traits.

Like many other pitchers in this organization, he added a sweeper this offseason which will give him something moving more right to left across the zone and my prediction is that it will grade out as his best secondary, somewhere in the 130 Stuff+ window. His command of the pitch, if his current command is any indicator, will probably need a bit of time to develop. The reason that a pitcher like Wesneski can command his sweeper so well is perhaps because of how long he’s thrown the same grip (more than 3 years). While in theory the sweeper makes sense for pitchers who already throw curveballs, there doesn’t seem to be a strong track record of pitchers putting the ball in the zone right after learning the pitch. Patience with the offering from an analysis standpoint will be key.

21. Ryan Jensen, RHP

Highest Level Reached: Double-A Tennessee

Four-Seam: 120 Stuff+, 47% In-Zone

Sinker: 95 Stuff+, 56% In-Zone

Cutter: 112 Stuff+. 43% In-Zone

Changeup: 99 Stuff+, 32% In-Zone

Slider: 116 Stuff+, 40% In-Zone

Curveball: 101 Stuff+, 40% In-Zone

Jensen has some of the best raw stuff in the entire organization. He has just struggled to put it in the proper locations, pushing his profile to some kind of reliever with the potential for leverage innings if he can muster even below average command.

Jensen’s stint on the development list last season saw multiple changes. The primary of which being a shorter arm action, increased velocity and a modified cutter. As a result, the Stuff+ numbers are in love. The data I’m using above to calculate his metrics comes from a sample of games to finish off last year at Double-A. There are even more aggressive numbers out there from Eno Sarris’s Stuff+ model that are based off some of his Spring Training innings this year.

There is, however, a baseline level of command a pitcher needs to get to in order to be a reliever at the major league level. That level is higher if you want to be a starting pitcher. Sitting below that reliever level of command, which you could argue is where Jensen currently sits, calls into question major league viability. But man, the stuff is so good here that I’m looking past the smaller issues with finding the zone. This is connected to how much I believe in Stuff+ as an evaluation tool. If I didn’t have Jensen inside my top 25, I would be a hypocrite.

The ability to fix a pitcher’s command is still something that feels pretty ambiguous, like correcting swing decisions for a hitter. It’s probably connected to repeatability mechanics (which maybe has a lower weight than the industry seems to think). It’s probably also related to velocity and movement (more velocity, more movement, harder to command). Some teams have internal command models that project what command should be based on the biomechanical factors of a pitcher and other variables. I’m unsure if the Cubs have something like this, but I wouldn’t be surprised if they did given their investment in markerless motion capture devices and the troves of information they probably have.

Jensen’s future rides on his ability to get his pitches into better locations. My bet is that the Cubs get him to the bare minimum for reliever command.

22. Cam Sanders, RHP

Highest Level Reached: Triple-A Iowa

Four-Seam: 110 Stuff+, 50% In-Zone

Sinker: 93 Stuff+, 50% In-Zone

Changeup: 130 Stuff+, 37% In-Zone

Slider: 103 Stuff+, 40% In-Zone

Sanders has an uncommon ability to both kill spin on a changeup, create lateral break on a slider above 82 mph and generate reasonable ride on a four-seam fastball. He’ll make an impact at Wrigley Field this season.

The debate of who has the best changeup in the organization comes down to Sanders, Wicks and my #30 prospect Luis Devers. From a raw data standpoint, it’s clearly Sanders. The command element of Wicks’ changeup boosts his total pitch quality to somewhere around the same as Sanders’.

The seams of how Sanders throws his changeup actually cause the pitch to drop more than you would expect. It’s not exactly like Devin Williams’ changeup, where he is throwing a left-handed slider as a right-handed pitcher, but Sanders’ changeup is a true swing-and-miss weapon that will give left-handed hitters a lot of trouble. Add to that a fastball with 17” of vertical break (ride), about 1 mph more than the MLB average four-seamer and a new sweeper slider that grades out above average and the mix here is exceptional.

Sanders problem entering 2022 was his command, but after transitioning to the bullpen it seemed like he was able to find the zone more. I scratch my head a bit as to how he wasn’t selected in the Rule 5 draft, but that could be a situation of other organizations not knowing he would be adding a sweeper heading into this season and the aggregate command numbers for 2022 not looking great.

Sanders is one of my favorite dark-horse players on this list to have a long major league career despite being overlooked in the minor leagues for a long time.

23. Caleb Kilian, RHP

Highest Level Reached: MLB

Sinker: 62 Stuff+, 53% In-Zone

Four-Seam: 95 Stuff+, 47% In-Zone

Cutter: 91 Stuff+, 45% In-Zone

Curveball: 76 Stuff+, 50% In-Zone

Changeup: 80 Stuff+, 38% In-Zone

If Kilian is to be a starting pitcher at the major league level, it’s going to be because of pristine location. The alternative is reducing his repertoire down and becoming a reliever. Right now, the better chance for impact is in the latter.

I might be out on a limb here saying the best bet for impact in a player like Kilian is to become a reliever, but I’m not totally convinced the stuff is good enough to work as a starting pitcher. The grades on his fastballs vary based on what Stuff+ model you’re using, but the two pitches that are closest to MLB average are his four-seam and cutter. Which are unfortunately the two pitches that are going to play better versus left-handed hitters, leaving him vulnerable versus right-handed hitters.

The further issue is that his stuff also lends itself to more contact than swing-and-miss. So with shifting restrictions and a location-over-stuff repertoire, he’s at a bit of a disadvantage, even versus the lefties his stuff is going to work better against.

My hot take is to turn him into a reliever leaning on his cutter and slider and try to get his velocity back up to 97 mph or higher in short-innings stints. I’m a bit surprised he hasn’t started throwing a sweeper, given his feel for a curveball and the need for more swing-and-miss. It could be because this offseason was spent tweaking mechanics, but that didn’t really stop the organization from giving it to other players with minimal time to ramp it up before the season got going. Kilian might be the rare arm that could actually get it in the zone at an above-average rate, a la Hayden Wesneski.

If you disagree with the reliever idea, and I’m sure the organization would tell me I’m crazy, that’s likely because the strike-throwing ability is exceptional. Why waste that on a reliever? My counter would come down to the variance of location and command statistics year over year. In a larger sample of pitchers, stuff does a better job of predicting future success. And stuff would get Kilian back to a level we haven’t seen in a bit.

24. Moises Ballesteros, C

Highest Level Reached: Class A Myrtle Beach

90th pct Exit Velocity: 103.3 mph

Ballesteros is a large man who hits the ball very far. If he sticks behind the plate, he is a top 15 prospect pretty easily.

As you may have noticed on this list, I don’t talk much about defense or try to evaluate it because I’m aware enough to know that I would just be regurgitating what everybody else says. I make observations occasionally watching games online and in person (Luis Vazquez is the best defensive middle infielder in this organization), and I’ll blend them in when I feel it’s appropriate. My strength is in interpreting data. Is Ballesteros a catcher long term? I don’t have confidence in saying yes or no. But I’m pretty confident I can tell you whether a guy hits the ball hard enough and at the right angles or whether a pitch shape will play at the major league level.

This rank is a hedge between Ballesteros coming off the catcher position and staying at it. He scorches the ball for his age. If you assume he gets more explosive by the time he can consume an alcoholic beverage in the United States, then you’re looking clearly at above-average raw power at the major league level. Mix that with a tame swinging strike and chase rates? This is a plus bat for sure.

But again, it all comes back to the defensive position. Off of catcher, he’d be lost in the shuffle of other big-bodied mashers who fizzle out by the time they get to Triple-A due to an inability to hit better stuff or poor swing decisions. At catcher, you can envision some kind of Cal Raleigh-type player. Raleigh is the Mariners catcher who hit .211 last year with a poor OBP but mashed 27 homers in 117 games to net above-average offensive production. Squint and you can see something like this down the road for Ballesteros.

25. Porter Hodge, RHP

Highest Level Reached: High-A South Bend

Four-Seam: 92 Stuff+, 55% In-Zone

Slider: 124 Stuff+. 35% In-Zone

Curveball: 83 Stuff+, 38% In-Zone

Changeup: 62 Stuff+. 29% In-Zone

Hodge was a pop-up prospect last year, a high schooler from Utah with a hard sweeper slider that decimated hitters. He’s headed to Double-A this year, an aggressive assignment, as he tries to corral his command into a starting pitcher.

Hodge gets the award for pitcher-I’m-pretty-sure-I-ranked-too-low heading into this season. It stung even more when I saw his assignment to Double-A to start 2023. My guess is the Cubs see something here that the public might be slightly behind on. It could be a usage tweak or an improved ability to put the ball in the zone, but it’s more than likely a velocity bump that would push everything he’s throwing up about 5-10 points on the Stuff+ scale if he were to tack on 2 mph.

This rank reflects the risk that he’s potentially just a reliever of some kind, with a nasty slider that would probably run up to 40% usage based on the numbers it showed against High-A hitters. And where he really wouldn’t need much command to be average with how good this pitch is. Its swing-and-miss rate hovered around 50% for parts of the season, which is more than 15% above the average slider for that level. The pitch actually gets a bit of “ride” which is a characteristic on fastballs rather than sliders (aka, it resists the downward force of gravity). But there is a subset of sliders like this which often perform very well.

There’s a shot he’s a starting pitcher here too. It’s based on an educated guess that the Stuff+ number on his fastball is misleading, thinking back to my earlier notes about how much starting pitcher performance depends on fastball stuff. That has to do with the natural cut the pitch has. It’s very similar to Justin Steele in terms of how it works, limiting contact as opposed to inducing whiffs. And Hodge’s ability to get it in the zone above 50% of the time is a really strong indicator that he may be able to throw enough strikes for a starter to emerge, even if he never gets to above-average command.

I don’t think he needs a changeup and I’m skeptical he needs a curveball outside of an early-count offering or something to work off high fastballs when he misses spots and wants to steal a strike at the top of the zone. A cutter or bullet slider would be the easiest thing to add and the organization won’t really do that until maybe next offseason. That would give him something to get under the barrel of left-handed hitters and induce whiffs instead of contact.

26. Jefferson Rojas, SS

Highest Level Reached: Dominican Summer League

Rojas mixed a great approach and a strong ability to make hard contact at the age of 17 in the Dominican Summer League (DSL). He was one of the best players from the Cubs most recent international class of signings.

This rank is a unique one for me given how data heavy my list is and how some of the data in the DSL can be funky in terms of accuracy. Rojas was a name that came up in two conversations with different individuals inside the Cubs organization when asked who they thought was an overlooked prospect with great tools. Given I hold the opinions of those two individuals in high regard, I decide to sneak Rojas onto this list in hopes I’m ahead of the industry in bringing his name into discussions.

His swing-and-miss rate was miniscule in the DSL and he mixed that with a contact rate around 50%. He’s in the same mold as players like Triantos and Piñango, with insane abilities to make contact but perhaps some need to refine that approach into a narrower window where the results would be more beneficial. His 90th percentile exit velocity was step for step with James Traintos’, of course against worse pitching in the DSL compared to Class A. And there’s up-the-middle potential defensively.

I would like to see Rojas start in the Arizona Complex League and make his way to Myrtle Beach. It’s a sneaky combination of contact and the ability to hit the ball hard.

27. Jeremiah Estrada, RHP

Highest Level Reached: MLB

Four-Seam: 147 Stuff, 56% In-Zone

Slider: 111 Stuff+, 32% In-Zone

Estrada has a huge fastball that bodes well for his chances of having a long career at the back end of a bullpen.

If you wanted to build a fastball in a lab and give it to any pitcher, you’d start with something like Jeremiah Estrada’s. It sits around 97 mph, but more importantly it has 20-plus of vertical break or “ride.” It resists gravity more than nearly any other fastball in the organization, resulting in a lot of swing-and-miss as well as pop-ups as hitters continually swing underneath the ball.

He mixes the elite fastball with a slider that possesses some of the same characteristics as Porter Hodge’s. It has an inordinate amount of lift to it, resulting, again, in swings underneath the pitch when at the belt, whereas most breaking balls create swing-and-miss underneath a hitter’s barrel.

Reliever depth is most indicative of an organization’s ability to develop pitching, contrary to the idea that it comes down to starting pitching. While starting pitchers hold immensely more value, teams that extract value out of developing and tweaking relievers end up simply with more impact arms at the major league level. Estrada is a byproduct of the Cubs player development and that is a wonderful thing to say after years of struggle to develop pitching (thank you, Craig Breslow and Co.).

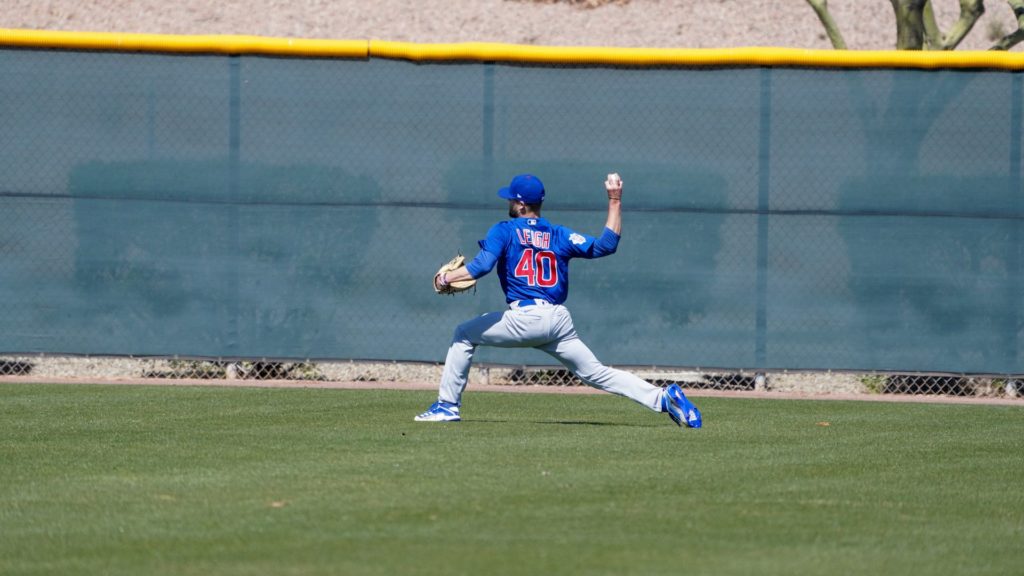

28. Zachary Leigh, RHP

Highest Level Reached: Double-A Tennessee

Four-Seam: 127 Stuff+, 60% In-Zone

Slider: 119 Stuff+, 44% In-Zone

Changeup: 80 Stuff+, 42% In-Zone

Leigh spins his sweeper slider up around 3,000 rpm consistently and has a quality fastball that he consistently gets in the zone. He and Estrada should be in the back-end of the Cubs future bullpen.

There are a lot of fun sweeping sliders in this organization, but Leigh’s is the most fun. It has around 18” of horizontal break on average, roughly 4” more than you’d expect from the average sweeper. It also hops between having some topspin and acting a bit more like a sweepy curveball against left-handed hitters while it tends to flatten out a bit more to right-handed hitters. The swing-and-miss rate on the pitch was a strong 42%, roughly 16% above what you would expect from the average Double-A slider.

Leigh’s fastball is also probably a bit underrated, given his smaller frame and lower release height, mixed together with a strong amount of vertical break, it approaches the plate at a very flat angle causing hitters to swing and miss at the pitch well above the Double-A average for a fastball.

Some validation of Leigh’s abilities is that the Rays were interested in trading for him at last year’s deadline. He should get to Triple-A this season.

29. Kevin Made, SS

Highest Level Reached: High-A South Bend

90th pct Exit Velocity: 100.4 mph

Made is an above-average defensive shortstop with a good feel for the strike zone that needs to tap into more bat speed in order to project as anything more than a utility middle infielder.

Made appears much higher on other industry lists, but my reliance on batted-ball data really forces me to question what the offensive median is here. Players like Traintos and Rojas possess such advanced contact skills and the innate ability to limit swing-and-miss skills that the tolerance for lower batted-ball prowess is higher. Made sits in an odd spot where all of the discipline skills are average–contact, swing and miss and chase–while his 90th percentile exit velocity is squarely below average for the level.

He is only 20 years old, so it’s crazy to think that the development of a player at this age is set in stone, but Made’s body is a lot more advanced developmentally than a player like Cristian Hernández, Jefferson Rojas or James Triantos. This creates some question about how much more explosiveness is left in the tank. I imagine he’s already gone through a bat speed program in the organization. And the issue with a program like that is that the quickest gains come in the first months of deliberate practice with the tools. Further refinement is more difficult to achieve and requires longer runways for improvements.

For Made to make me look like I’m clueless with this rank, he’d have to flash a plus-plus glove (which he’s short of right now), especially given how the shortstop position at the major league level has developed to focus on impact bats.

30. Luis Devers, RHP

Highest Level Reached: High-A South Bend

Four-Seam: 61 Stuff+, 51% In-Zone

Sinker: 62 Stuff+, 52% In-Zone

Changeup: 97 Stuff+, 44% In-Zone

Slider: 85 Stuff+, 47% In-Zone

Devers won the organization’s minor league pitcher of the year award thanks to advanced feel for a changeup that High-A hitters had legitimately no idea how to counter.

Devers snuck his way onto this list after news broke that Nazir Mule went down with Tommy John surgery. His changeup is filthy, regardless of whether the data isn’t totally in love with it like it is in love with Cam Sanders’ changeup. But the results on Devers’ cambio are impossible to overlook. It held a 45% swing-and-miss rate, 11% above what you would expect for the average changeup in South Bend.

The reason Devers is 30th relates to the lack of another intriguing pitch. His fastball averaged 90 mph last season, neither his four-seamer or sinker have the shape to excel on their own without 6-7 mph of velocity. His slider was more of a curveball around 75 mph. There are organizations that prefer a pitcher like this, one that can command the zone and already has feel for a changeup, where they can build the rest of the repertoire over time, but I do think the hardest thing to develop is fastball shape. And to project as a starting pitcher, as I’ve emphasized throughout this article, there needs to be a strong fastball shape or excellent execution like Wesneski (and we usually don’t believe the latter is true until we see it at the major league level).

My expectation is for Devers’ velocity to be up across the board. That would make me keep close tabs on him. Something like a Kohl Franklin velocity jump, which was 5-plus miles per hour in a matter of 2-plus years, would be a great recipe for a top 20 spot on this list. But until then, I’m comfortable leaving Devers more on the peripheral.